serenity

It's been a while, hasn't it? Towelket Fury was something that loomed over my head for a long time. It's been several months now since I last played a game in the series (or made a writeup on anything, for that matter). Life does get in the way, but pertaining to Towelket and particularly Fury, there was something holding me back a little bit, knowing what was coming. I had only fleeting ideas of what to expect, only hearing this shared sentiment that this game was something to behold. The mystique of this game was undeniable, and that is not something that was lost on me going into it. Out of Kanao's output, this game in some sense serves as one of the figurative markers upon the trail, in the same vein that 2 and 3 are praised for their gut punches, in the same way future entries are lauded, this is one that I believe holds a particular weight towards it for a number of reasons.

Again, this mystique. A game full of disturbed content. A game that was taken down by its author, for reasons unbeknownst. Was it because the game was a broken, buggy mess beyond belief? Was it just too extreme? Were these ideas presented in this game a point of shame? Although it was only very recently where Kanao was comfortable with this game streamed or recorded in any capacity, why is it that they wanted to put it behind them so badly?

I don't intend to explore that particular aspect of this game, because it's a rather frivolous thing to expound upon for the purposes of what I want to write about, here. Rather, I find myself more concerned and grossly invested in the grand context that's been building up over the course of these earlier entries in the series, the themes that have been cropping up and been ever persistent: Bodily agency, motherhood and the figure of the mother, and above all, this sharp focus on pedestalizing the image of the virgin, the chaste and conservative woman. These are all taken to their extremes with this game, themes that weren’t lost on me playing the previous entries, particularly 6– which I feel like this game definitely draws a lot from. Every extremity in regards to these themes is presented without any recourse. In other games, even in moments of silence, there is still hope, there is still love to be found. But this? This game is a resounding, angry and coarse scream into a vast and lonely emptiness.

I will be starting with a synopsis. I really do want to try to contextualize everything I can here since it will be important for the sake of talking about what I saw in it. Feel free to skip ahead or skim, as I really would like to be meticulous with describing the events of the game just to benefit the discussion of the themes underlying everything.

Just to briefly touch upon the actual gameplay before I dig into the plot, it is the usual RPGMaker affair. There was something a little bit different tried here with an incorporation of affinities– there are weaknesses and resistances to different elements and physical attack types– but this is something that is brute forced later in the game and only really matters for the start, where it adds a degree of friction trying to reorganize your equipment before every boss fight. Aburaneko is there to just outright tell you these affinities as well, so there isn't much to intuit. As was the case before, the actual RPG part of this game is just something that is there, and that always has been the case. There is a severe lack of signposting in some parts, but that's something that I just expect from these games at this point. Rather, it is the narrative of these games that concern me, above all.

I've made a lot of complaints about the previous games overstaying their welcome, but this game takes things into the opposite direction– the actual narrative and game length are trim, and all the events in this game, I feel, have some sense of purpose. I was able to complete this game in about two and a half hours, and a good half of that felt like it was dedicated to wandering around for the next trigger point, and towards battles. It's hard to say if this was a matter of course correction or not or if it was just a matter of a very short development before the game was put out, but it definitely went far in the direction of Towelket 3, maybe even further than that. There are a lot of interaction points still present in the maps that just don't work at all, and dialogue in this game with NPCs is as dry as it gets or just lacking even with actor sprites wandering about, which is a sharp contrast to being drowned in flavour text and one off sex jokes present in the entries of the past. I'll touch on this more in just a bit.

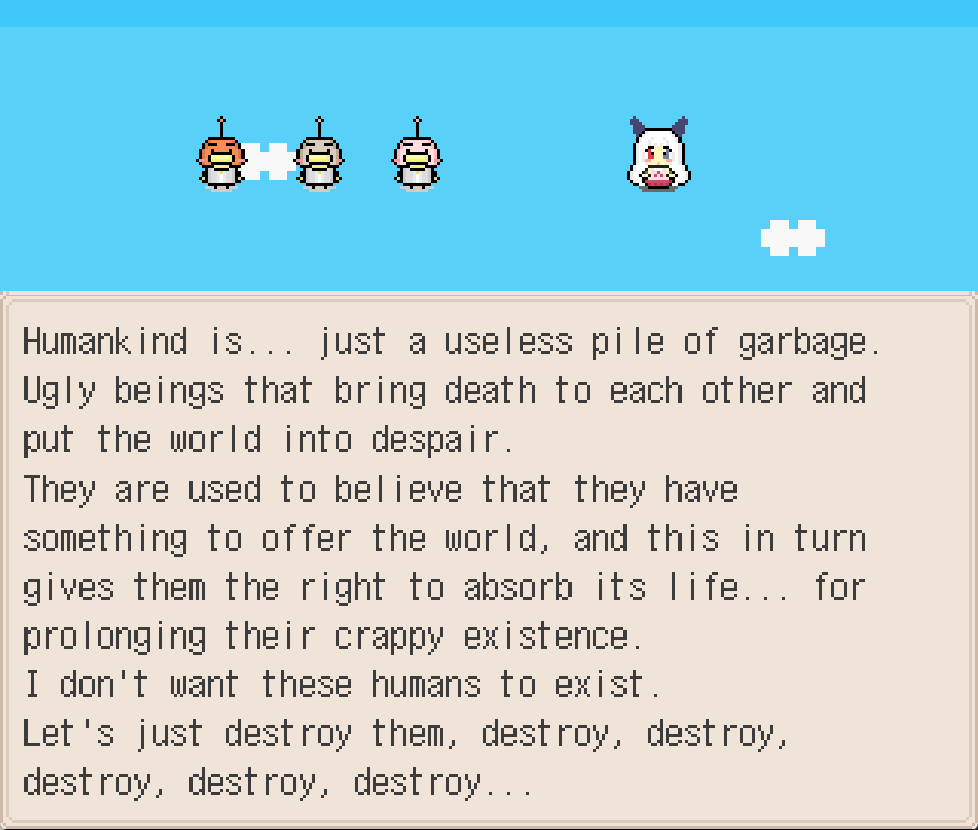

The opening prologue scene has this game show its hand immediately. Towelket 6, for comparison, takes a little bit of time with the opening to lead up to violence, but here, not so. Paripariume and her sister, Pucchi, are paying respects to a grave atop of a hill. She brought her two children along. This map has been reused many times over at this point and always serves a degree of importance. Towelket 2 positioned it as a quiet, somber afterlife, for lovers to reunite after their turmoil. Towelket 6 desecrates this iconography after Warawau knocks out and has her way with Minpou. This same desecration occurs here, and the irony of it being PPU who dies in record time this time around is not lost on me. Her baby basket is approached by a bird. Thinking it's benign, Paripariume calls out to it, but one of the babies is killed by the birds. More swarm in, laughing in manic unison, and kill Paripariume. In her dying breath, Pucchi returns to take the remaining child to safety. This child is Kachiru, the protagonist. It's established right at the start that there will not be any room to breathe.

After this, we skip ahead in time. Kachiru is now a school boy, in class with two girls-- Roppenchu and Ponpe. Chapter one's backdrop is that of the same pastoral town map, reused for the nth time from previous games, although there are some things to note in this iteration. The town is cold and empty. Outside of enemy encounters, there is nothing here. No villager NPCs, just basic placeholder shopkeepers with absolutely nothing to say. There are mini-locker hammerspace dungeons you can go through for loot but they don’t even attempt to contextualize these.

Even after acquiring your first party member, I noticed a sobering lack of interaction points anywhere. The only beacon of lights here are the two girls, Roppenchu and Ponpe. You have the choice of one to bring with you to the Constellation Day viewing-- a day where spirits of one's most closely departed returns to Earth to convene with the living, and where lovers confess to one another. Both girls are smitten with the protagonist, and whoever you choose, it is with them that love is professed atop of the protagonist's house, drawing that same imagery of the love confession from Towelket 2. For the intents of the remaining plot summary, I'll be referring to the first love as Roppenchu, as that was who I selected on my first playthrough.

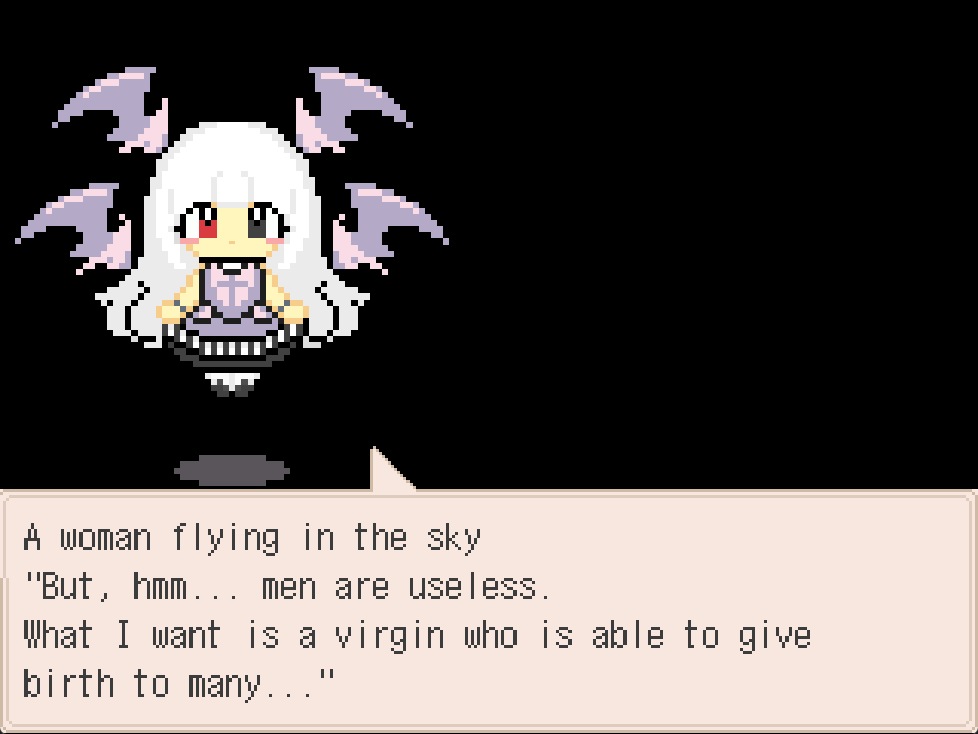

After this, it doesn't take long for an upheaval. The next story event goes back to the hill, where Paripariume's spirit lies in wait for Pucchi and for the protagonist. Roppenchu is there to spy on what happens on the hill, for some reason believing the protagonist to have some Freudian complex towards Pucchi (a typical assumption to make about someone else, at least in the bizarro world of Towelket), but after Pucchi explains Paripariume's passing, the antagonist reveals herself here, searching for a virgin girl for her schemes:

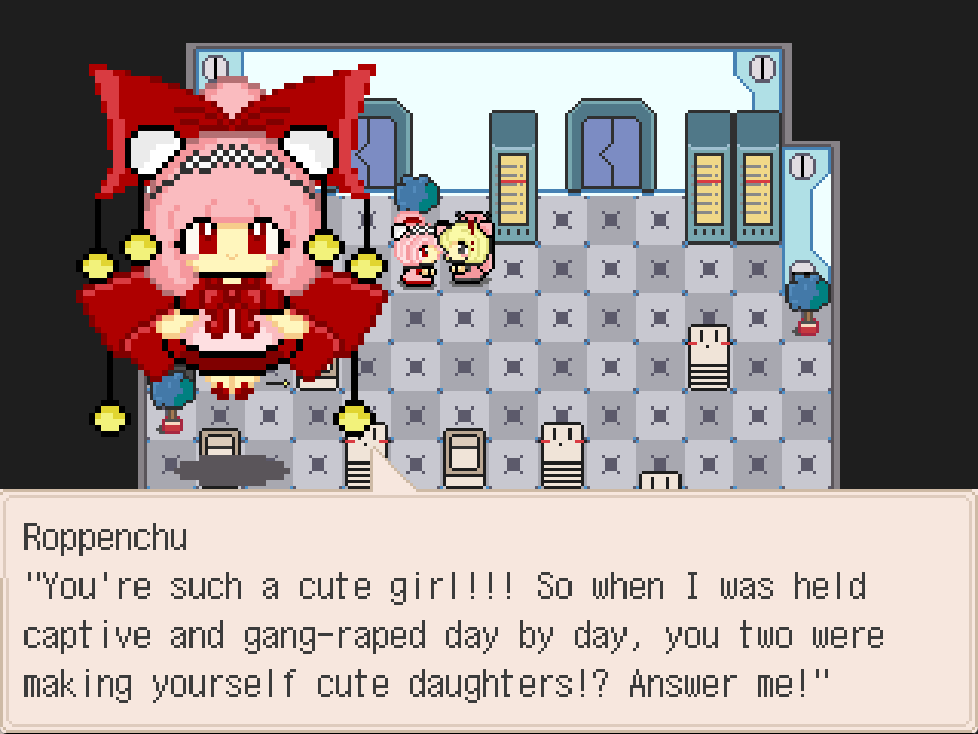

It's Nyanyamo. Nyanyamo, the same girl from Towelket 6, who was helpless to the whims put upon her. The same Nyanyamo who was raped, desecrated, turned into an object of desire, forced into the role of a mother against her will, forced to give birth, a girl utterly destroyed-- and now, in an utter reversal of role, reflected by her now pastel, inverted palette, she is the proponent of what she suffered. She captures Roppenchu, forcing her into the same role she once played. That of breeding stock for birds, to be violated without recourse, and to propagate human-bird hybrids, using the duck-like aliens from 2 as the basis of the "alien" threat of this game

There is a time skip, after this. The protagonist marries the girl that wasn't selected at the start of the game. Picking Roppenchu at the start would mean that Ponpe serves as the wife in this case, but as indicated by chapter two's title, it's nothing more than "a reluctant marriage." Ponpe knows that the protagonist's affection towards Roppenchu still hasn't faded away, but chooses to live on with them because Ponpe still harbored feelings from childhood.

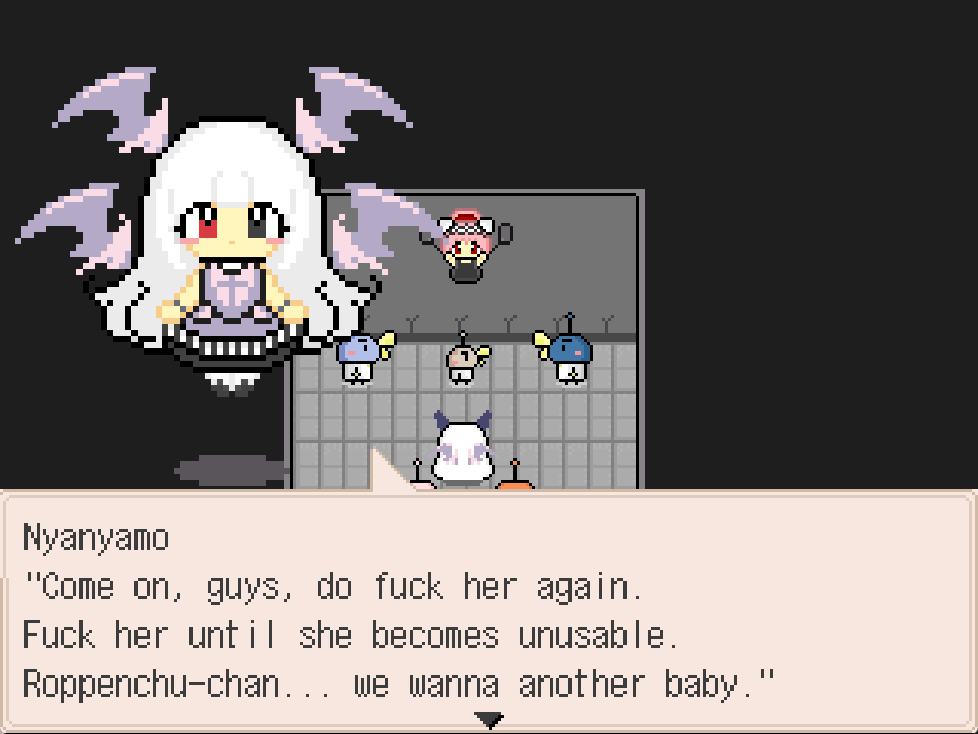

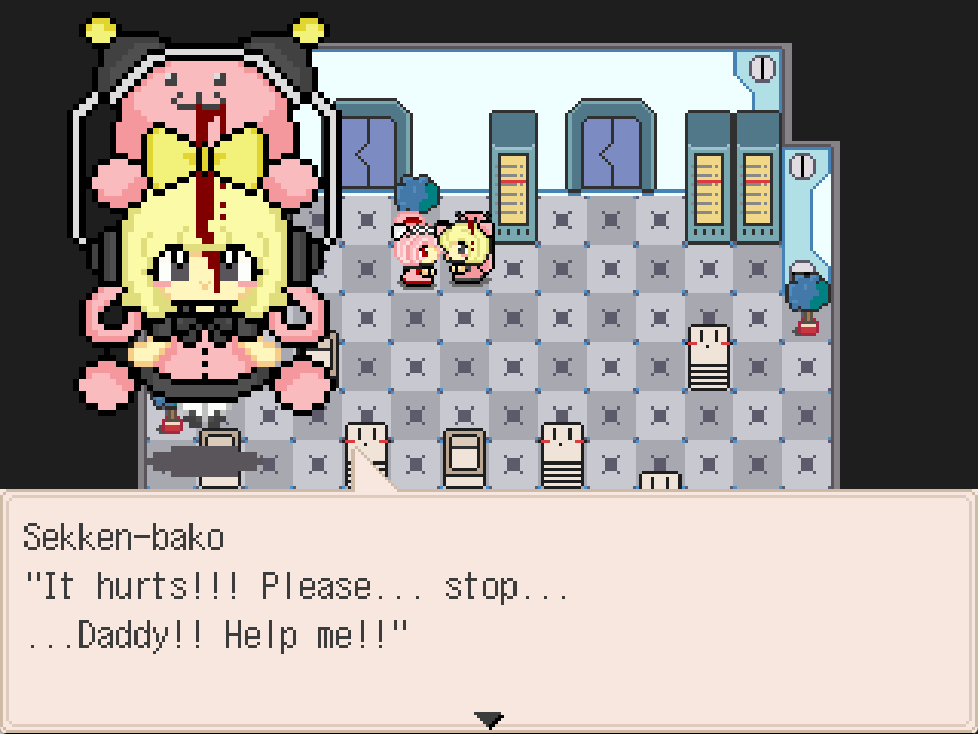

This all runs in parallel to Roppenchu's plight. She's hung up in a cold, utilitarian room. Her torture is shown in excruciating detail. Nyanyamo chastises Roppenchu, talking about the sounds she made while she was forced. Roppenchu is chained to a wall in the same way those Conchelle dolls from earlier games were hung up, and you just sit and just... watch, witness this dialogue chiding her, all as she births out an alien child, all the while one of those stock RPGMaker screams plays. The subject matter on display is in such a sharp contrast to the sprites, especially with the chibi style sprites just smiling away while all this is happening… this is what this series is known for, but here? It feels like this contrast is at its most polarizing extreme.

I feel like that is something Kanao excels at. That contrast, that discrepancy between subject matter and artstyle. Their sprite work, especially in these earlier games, is very lacking in details, and the chibi portraits are as cutesy as it gets, with cute little gaudy ribbon and heart flourishes dangling about. The same goes for the actor sprites, being just about as simple as it can get as well. And yet, even so, these displays of violence just feel so much more graphic despite... Well, lacking in graphics. But I digress.

Roppenchu begs for her death after this birthing scene, a luxury not afforded to her at this point. These hybrids she is forced to mother are to eradicate the human race. Nyanyamo’s reason for doing this is multivalent. The clear, outward purpose of this is to act on her nihilism. She feels like there is nothing of value in humanity, in people outside of her closest circle– a space she only shares with one person, Okowa, who she kills without hesitation later on down the line when she feels like she was “wronged.”

Nyanyamo was brutalized in the same way, shown in flashback to be taken captive by birds, mocked, tortured, raped, but in her case it appears to be for nothing more than the a sick, hedonistic pleasure– no grand design of destruction or anything else like that. The dove harlot sisters from Towelket 4, Poppochi and Kazue, reappear here as well, initially acting as Nyanyamo's tormenters, later her lackeys. Nyanyamo perpetuates this cycle of violence-- a cyclical violence, in every manner possible upon the body and mind itself-- and wishes to inflict it upon humanity and use the girls she captures as nothing more than playthings as if to reenact her own trauma and imprint that unto them. The only solace Nyanyamo has is with one of her captors, one who is smitten with Nyanyamo-- that being Okowa, someone meek, who wants nothing more than to be friends, and later, lovers with Nyanyamo. The two eventually engage more intimately, sexually, with one another, something framed as manipulative on Okowa’s part for taking advantage of Nyanyamo in an already damaged mental state. Even in spite of this connection, Nyanyamo acts solely on her rage.

Agochu is introduced before the sci-fi apocalypse of this game occurs, being a friend of Pucchi's. It feels like these two are inseparable at this point, and she's positioned in the plot in a similar manner to 6-- being a sort of figure that aims to solve or mitigate the apocalypse. The two of them help organize a safehouse in a hammerspace locker for Kachiru and Roppenchu, and another time skip occurs. The protagonist and his wife survive in this safehouse, and even have two children together. The most recent one is a baby, while the other child is a party member and their appearance and character are dependent on who you marry. In this case I will be referring to them as Sekken-Bako. The protagonist and his wife go to fetch milk, while Sekken-Bako stays to watch the child. Pucchi is revealed to be killed in a subsequent scene, however, and while the milk fetching is occurring, Agochu diverts power from the safehouse to transfer Pucchi’s soul into a Christmas-tree shaped robot, compromising the safety of the two children, and they are found and taken away. Sekken-Bako is saved, but the baby is captured. And then we have the baby scene...

Starved and broken, Kazue presents Roppenchu with a human baby. It’s the baby that was kidnapped, Kachiru and Ponpe's baby. The baby of Roppenchu’s first and only love. Kazue eggs Roppenchu's hunger on, and in her desperation to survive, she grabs the baby, and eats it. In the other Towelket games, events like this are usually accompanied by a fade to black, but here, you are just made to witness this. And it lingers for a painfully long time. Kazue laughs sadistically at the scene, even mentions how Roppenchu isn't even listening anymore because her hunger is so ravenous. And it only gets worse. Roppenchu is saved by the group, briefly, but after seeing the protagonist with his wife, she goes mad, beating Sekken-bako, in whom she sees Ponpe’s image, and runs off. She is recaptured, and interrogated. Roppenchu doesn't budge from here, though-- she is broken. So, limb from limb, she is dismembered, torn apart, left to barely hang onto life-- something Nyanyamo revels in.

The next time the protagonist finds Roppenchu, she is nothing but a disembodied torso and head, hooked up to a machine to grip onto whatever life is left. She is put out of her misery, here-- similar imagery to the final moments of Towelket 2, and just as was the case for that game, the protagonist embraces what remained of their first love. That was the ending of Towelket 2. So surely it would end here, right?

...Not so. There is still more, here. There's another factor in play here. The protagonist is already married. And yet, they are still smitten with someone who is nothing more than a corpse in the ground, shirking a grand Adam and Eve-esque “responsiblity” put onto them by Pucchi and Agochu to repopulate the planet after its apocalyptic culling. The outside world is still dangerous with Nyanyamo still roaming about, but now there is a rift. A rift between Kachiru and Ponpe, as well as their daughter. This disruption of the marriage is something that drives Agochu to act out in a fit of madness. I'll try to keep the description as short as I can here. The details are a bit crazy, so please bear with me.

Sekken-Bako is captured by Agochu, and has her womb removed, due to the fact that a parasitic clone of Roppenchu that was created by Okowa came into contact with her and likely implanted a parasite into her to propagate further. It is also revealed that Pucchi was actually made to be killed on purpose, so that her soul could be transferred to a robot, while her human corpse would be made to create flesh clones to act as vehicles for breeding. Effectively, Agochu was committing the same crimes against humanity as Nyanyamo and the birds were, albeit with a colder conviction for the sake of “saving” humanity instead.

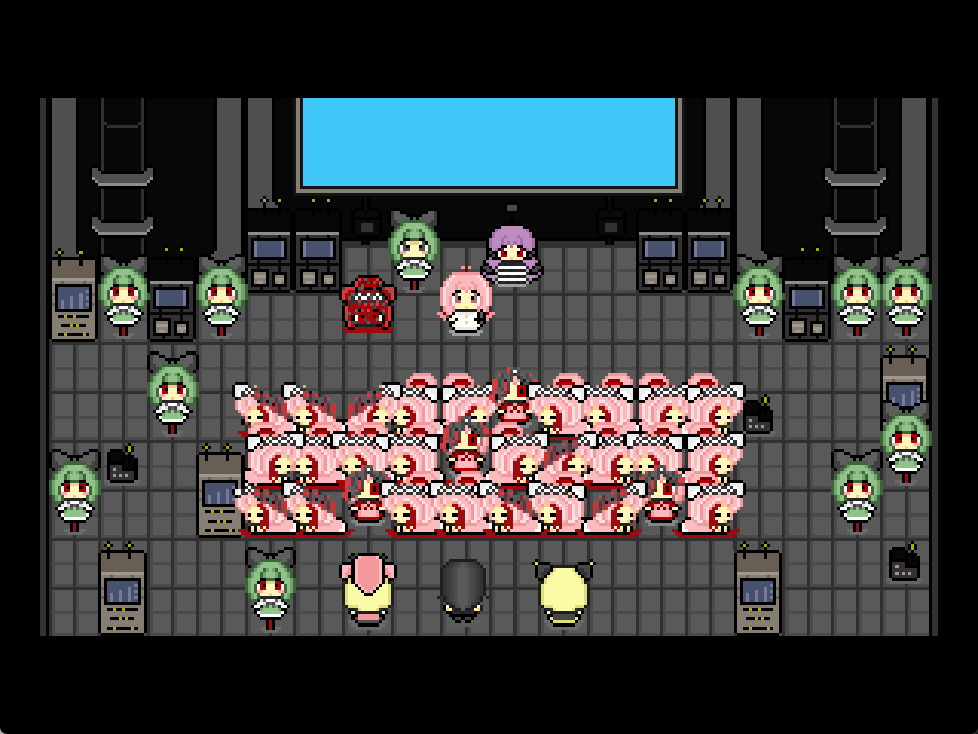

Through these experiments, she discovers a sort of telepathic connection between birthed hybrids and the mother. The Pucchi clones die upon childbirth, and as a result, the hybrid babies die as well– this is something that happened to many of the hybrids wreaking havoc on Earth after Roppenchu dies. With the severing of that connection to the mother, the clones die. To act on this discovery, she teleports to Nyanyamo's base of operations with the aim of killing all of the humans who birthed a hybrid. Okowa, Nyanyamo's lover, is captured in the process– and is forced to create more clones from the corpse of Roppenchu for a further scheme.

Of course, Agochu did all of this for a reason, even if the steps needed were utterly nuclear. Gathering all of these clones based on the protagonist's first love, she draws the protagonist into the bunker, and presents him with all of them. She pulls out a machine gun and shoots all of the clones dead in front of him. She did a horrible thing to Sekken-Bako, and to Pucchi, so in the end, she shoots herself to atone, hoping as well that this gesture would prove to the protagonist that he should move on from what is already long gone, and love what he has in front of him.

So surely, now, all is well? In spite of the nuclear solution, this gambit from Agochu does bring the family back together, somehow. But things aren't over yet, no. Nyanyamo and Okowa are still alive. Their plans are wholly thwarted at this point-- Agochu killed every last woman taken in to make hybrid children, which means that there are no more hybrid aliens, and no more women that are “defiled” so to speak. Okowa admits defeat, but Nyanyamo doesn't. Nyanyamo, this whole time, believed Okowa to be a virgin girl-- just like the other mothers, and demands Okowa be used to breed children to further her plans. Okowa rejects this motherhood, however, not out of lack of desire, but rather, because she isn't a virgin-- which doesn't deem them a suitable canditate for hybrid breeding. In spite of what love existed between the two, however, the discovery of Okowa not being a virgin causes Nyanyamo to kill her on the spot.

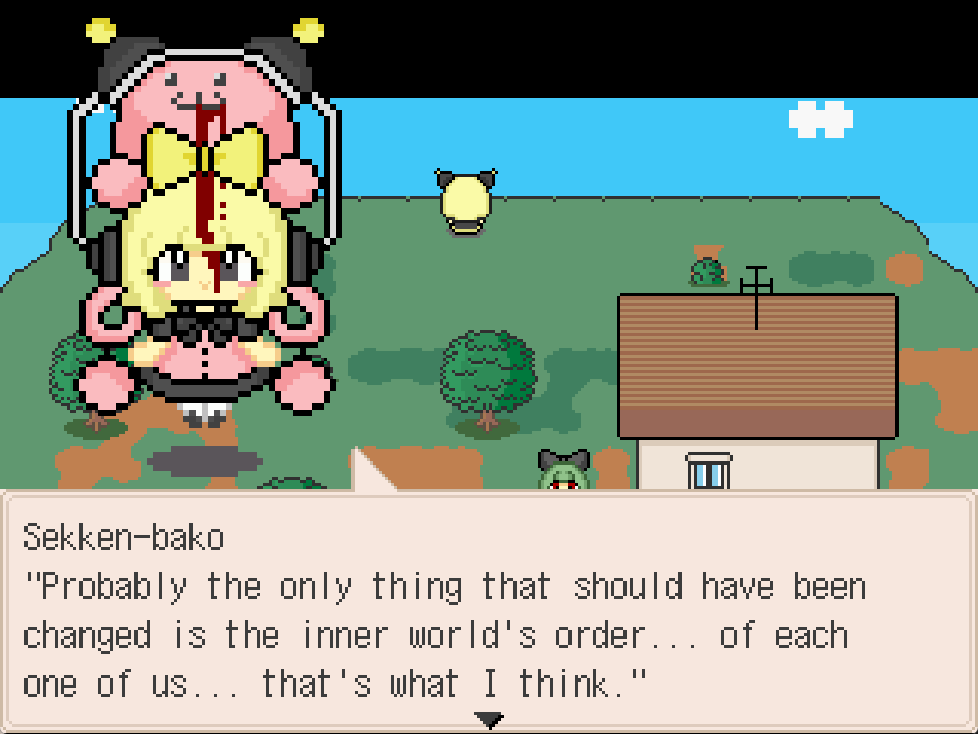

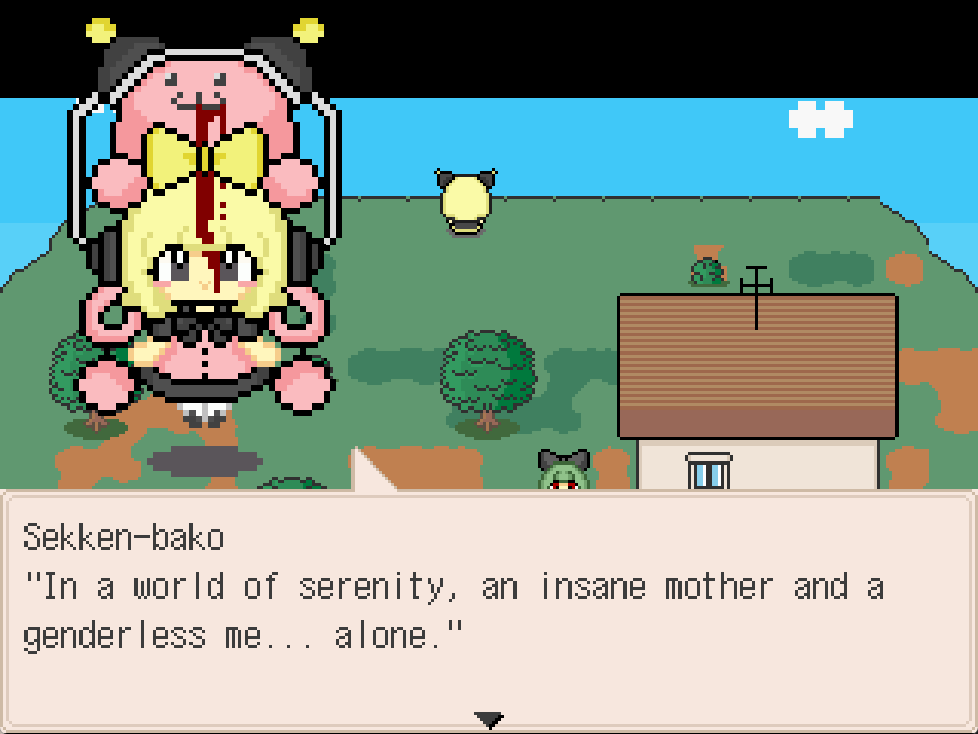

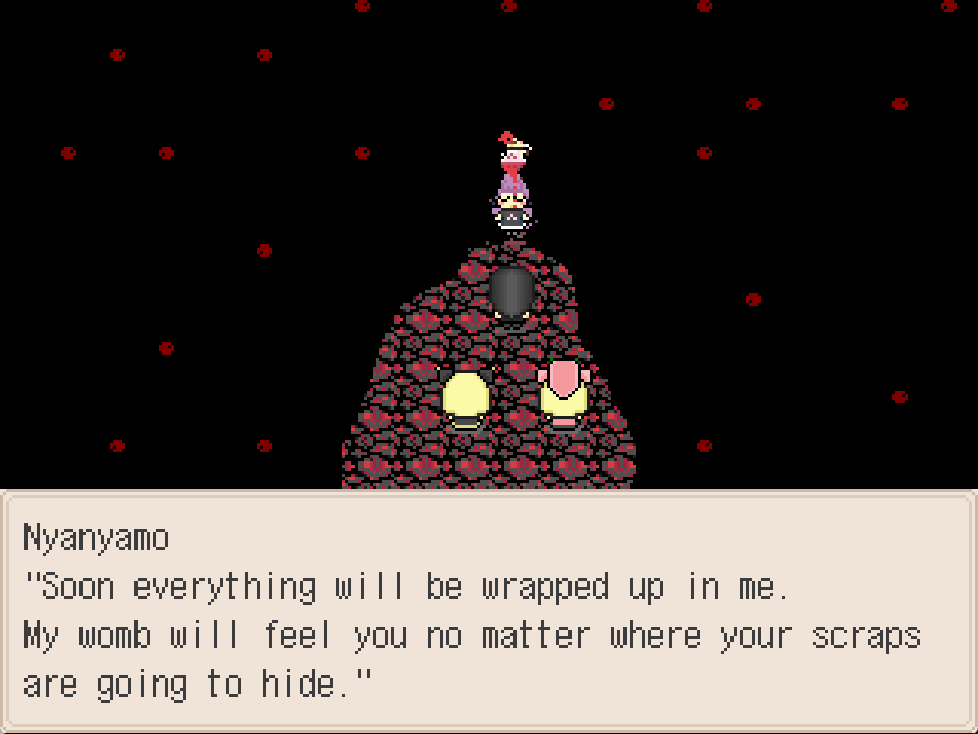

And so, we move on to the final chapter. This is when the game starts collapsing in on itself. The town outside of the lab has become a crimson red ocean of flesh-- this is outright stated to be a representation of Nyanyamo's entire sense of self enveloping the town, a return to the womb. The protagonist's family finds Nyanyamo, represented as a uterus merged with the still corpse of Okowa, and have the last fight in the game. Killing her causes the protagonist to become enveloped. He does not die, but instead becomes a part of Nyanyamo, a part of the world, still breathing, but unable to act. The remaining survivors, broken and alone, find a faraway place to live, but at this point, both Ponpe and Pucchi are broken and silent, and Sekken-Bako, with a devastating clarity compared to her both her mother and grandmother is a somberly acceptance of the fact that she will be the only one on planet earth, utterly removed from gender with her womb removed.

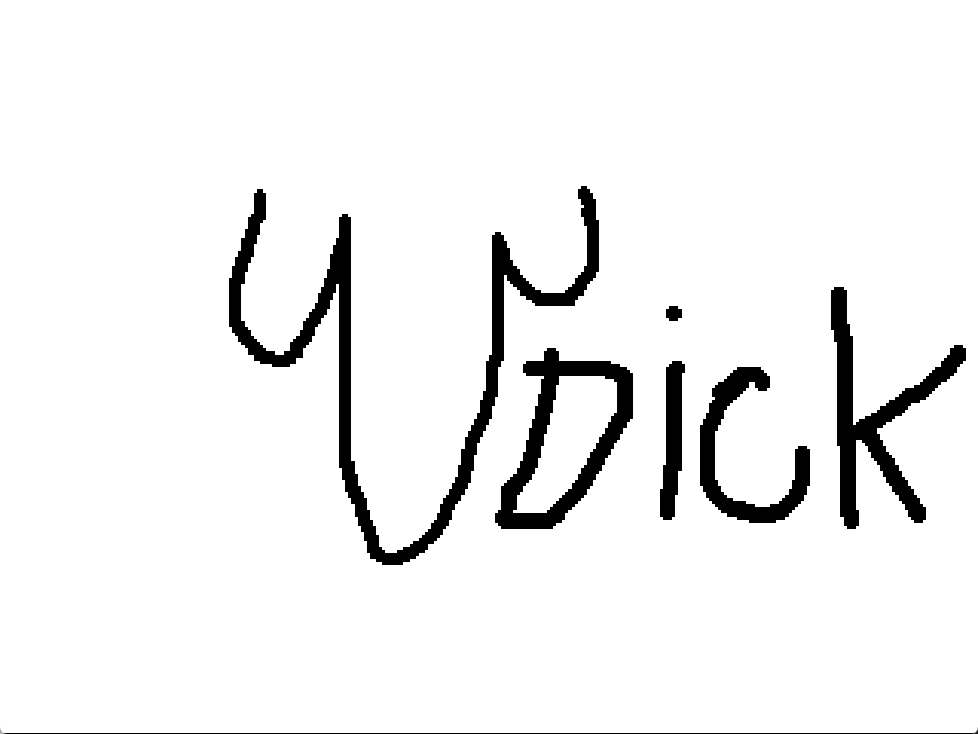

... And then, after all that, if you purchased the Just Kidding item for the alternate ending, we have the deepest undercutting post credits scene in the series so far. The joke ending is one of those “it was all a dream!” endings, being a wet dream that the protagonist had. They outright break the fourth wall, congratulate you for playing this piece of shit game all the way through, calling you a psychotic pervert for probably finding some sort of sexual gratification out of the torture Roppenchu went through. You then get an MS paint drawing of a penis as a “reward” from the protagonist himself.

Yes, that is a screenshot from this video game. Towelket Fury.

There’s a lot to touch upon here, and I think an apt way to start is with the end. Specifically, the joke ending, to call attention to this built up continuity of violence that we’ve seen thus far with these games.

I would put all my chips onto the table to say that I think the joke ending of this game should have just been the real ending, no pretense, nothing. Because as outlandish, irreverent, and disgusting of an ending this is, there is something so… Angry behind it, something so sinister. Because as much as Kachiru speaks in such an irreverent tone about beating off and getting one’s own rocks off to all of the sickening imagery in this game, these words are something that draw attention to something very specific, I feel, and that’s the gaze of the audience.

I can draw a parallel to Michael Haneke’s Funny Games. There are two films titled this, but they are under the same namesake and director, with the one coming later being a shot for shot recreation. They are violent, home invasion horror slasher movies. They were meant to invoke the usual tropes, but as it goes through the same motions of slaughter and torment, it illuminates all the hallmarks these films go through– pain, death, and notably, a very useless male lead (in the case of these films, the father) who almost seems to be wiped from the screen, like air, all the while the female lead is set to suffer. Sounds familiar, no? All the while having the main antagonistic force of the game, a set of twins, act in complete friction to audience expectations, even breaking the fourth wall at many different points– drawing explicit attention to the slaughter to make sure it “looks good for the camera,”, literally winking and nodding at the viewer, and, even at one point, when odds are twisted and one of the twins is killed, the other literally pulls out a remote and rewinds the film such that their twisted “game” can continue onwards. All for the sake of putting on a “show” for the audience– after all, that’s what we come to watch such films for, no? Blood and guts, violence, torment. A twisted game enacted for our own gawking and sick pleasure.

Think of other RPGMaker games, specifically, horror ones: Not enough kills. Not enough kills. Not enough kills. A fitting title for the final chapter. What do we expect from games of that ilk? Death scenes and a subsequent game over, but here, there is no such luxury afforded for the female protagonists we follow. They persist even after they are reduced to nothing. As the world of Fury collapses in on itself into a pile of throbbing flesh, as the game presents its utmost visual form of friction and contrast, as… uh, the arrows indicating how to move to the next screen blend in with the background… this is the ocean sea of blood, corpses, and tears we have been bearing witness to for these past couple of years of Kanao’s output up until this point.

Fury does not relent, not for one second. And any opportunity we are given to breathe and see something human with heart on display, it is immediately undercut. Nyanyamo kills Okowa, her last vestige of humanity, and even in flashbacks where they profess their love, the two of them are so blinded by sexual desire. Pucchi, who did nothing but sacrifice and act selflessly throughout this game, had her corpse used as a template by her best friend as a breeding pod, and her remaining consciousness is an immobile robot husk. And mourning from the protagonist for the one they loved in the past, a moment that held such weight in Towelket 2, was framed as an unmanly and unhusbandlike thing to do in the context of a marriage. Humanity, in this game, only shines through when it is at its solemn end, coming from a character who arguably had their humanity, their gender and identity, completely stripped from them. It feels, to me, like Kanao wrote all of this game with a sense of indignation towards the audience, in the same regard that Heineke does in Funny Games. As if to say, “how dare you get invested in my stories, in this suffering? Is this game more of what you want to see?!” But all of this is with a clinical precision, a sharp self-awareness that bites and cuts into the creator’s own skin– because why else would that joke ending exist? And perhaps that is also why Kanao looked at this game with some ire after its creation… But that’s only a mild conjecture on my part.

But with all this being said, this joke ending almost keys to me that a lot of these ideas of violence, agency, motherhood; all these were things that Kanao desperately wanted to purvey, to the degree where it came to appear as outright venting to an extent. There are brief character asides where it almost feels as though they are being used as mouthpieces– the daughter’s final speech and Nyanyamo musing on humanity come to mind. With that being said, this explosion of violence and filth, only to just undercut it all at the end– it reads as though this progression of pain and suffering they’ve built up for their characters over the course of all these games was leading up to this only for it to boil over the pot, figuratively, and just left to well and sit. Towelket 2 was a game, for some time (not so, now, considering a remake is on the way and Dekapari exists), that Kanao felt some shame about, and it makes sense to me that after this, they changed trajectory again to embrace irreverence again, because in earnest, the joke ending kind of shows itself as a self-aware nod that this series has been devolving into some degree of sufferporn. Not to say that is a bad thing, of course, since this outlet has been a wellspring of ideas that I simply just have not seen explored in games at all. We just had to leave it to something that on the surface appears like a cutesy little romp to show them to us.

There is the namesake of this game, as well-- Fury. Why Fury? There is an anger that permeates through the seams with this game, but I wouldn't be remiss to draw an allusion to the Furies of Greek myth-- Goddesses of vengeance who wreak torment and suffering upon their victims. An act of insolence, met with being hounded and destroyed-- that is what caused Roppenchu to be captured to begin with. After all, acting upon a perverse curiosity was what set off these events and, perhaps by extension, a premarital absconding atop of the house after Pucchi asks the two young lovers to get down could have been the grounds for this, as shallow as that might be. Furi Kusukusu from Towelket 4, who shares the same wings and sort of purple palette as Nyanyamo in this game also gives some credence to this, in my opinion. She acts the same role, admonishing and physically torturing Koucha for her involvement with Moca, for defying her own people for the sake of love. In the case of Nyanyamo, her acting out as an agent of vengeance comes as a due consequence of the pain inflicted upon her. A lashing out towards the world and the order of things itself, rather than that of a specific targetting.

Then to touch upon the representation of gender, and gendered subject matter like the presence of sexual violence towards women and motherhood– I’d like to call attention to the regular ending– where the daughter, her womb removed, remarks on the world where gender is removed. Here, there is no room for violence. There is peace and serenity here, but it is a lonely, and cold. The daughter, Sekken-Bako in this case, is the vessel for this lineage, and she holds all of the trauma of this game in her heart– this is why she speaks in such a wisened sobriety compared to the more innocent heart she possessed earlier on in the story. In spite of the nihilistic worldview that has been exposited that serves as the basis of the apocalypse of this story, this ending serves as a form of acknowledgement of what kind of world would result from this gendered apocalypse in a sense: Kanao has the foresight to show this empty sense of serenity that would result from the removal from the paradigm of man and woman is to be removed. What was supposed to be set up as an Adam and Eve renewal of the world, a form of “order” meant to be restored, was disrupted by Nyanyamo– and in doing so, there is no more opportunity for violence. Perhaps in that sense, Nyanyamo’s nihilistic goal was achieved. Mankind is destroyed, because there is no more violence– that is, after all, what Nyanyamo believed all mankind was good for.

So now it would be fitting to move onto the omnipresence of sexual violence in this narrative. Something that served as a catalyst for the slaughter in 6– this has become a multivalent continuation in a sense. A cycle of violence that has persisted even beyond games. Kanao presents rape as one of the highest form of violence that damages and destroys one’s own identity and sense of physical being itself, a harrowing mental ordeal that lasts and permeates even past one’s own lifetime. The aftermath spans past games, even. Think back to Towelket 6, and Warawau– what was imprinted upon Warawau was something that was imprinted upon Nyanyamo in that game. Perhaps that is why the only time Warawau saw something in Nyanyamo was when she saw her in absolute ruin, surrounded by children she was forced to birth. And perhaps this is why Nyanyamo occupies an eerily similar role to the one who treated her like human filth in a different continuity, acting out sadistically as if stripping away Roppenchu’s bodily agency and worth is something that is a necessity. And this cycle of trauma is perpetuated later by Roppenchu, as well. Even after being saved, seeing Kachiru and Ponpe's daughter sparks a violent urge, hurting Sekken-Bako and running off even after being saved.

The role of the virgin and chaste woman in this game, as well as the other games, is that of something worth aspiring for. An aspiration to be, an aspiration to maintain, and sickenly, an aspiration to defile. Parpariume in Towelket 2 was one such woman. Love persisted even in such a case, but the way she viewed herself after everything was miserable to behold. This chaste, woman is often presented as something for our Towelket protagonist to fawn over, but at the same time, one that is… sickenly, worth their weight as breeding stock for the alien threat. But this tying in of this sexual element does key in a disturbing reality that perhaps that “chase” the protagonist is undertaking would not be dissimilar to the way these virgin women are valued for their womb by the villainous faction. Nyanyamo loved Okowa, this is undeniable, although the context of it is something that is owed to something akin to stockholm syndrome and sexual desire. But even so, Okowa being revealed to not be a virgin is something that just causes Nyanyamo to lose what was the last vestige of love she had for the world, because to Nyanyamo, there is nothing left to be loved in a woman that is impure. A woman that is impure has no worth as a mother. One could also read that Nyanyamo she sees too much of herself in Okowa, which I believe wouldn't be beyond her if the precedent for her destruction is to repeat this degradation that occurred to her unto other women: so in a violent fit of self-affirmation, she kills her, and melds together with her in distorted form.

Overall, Fury feels like it tries to execute some of the same ideas as 6-- notably the ones pertaining to Nyanyamo. And I believe this is the culmination of those ideas, taken to their extreme. A game of extremity. I understand that this game might be viewed as edgy, but considering everything that came before… To me, this is the zenith. Fury undeniably ends up feeling like its own thing rather than being a complete retread. I’m glad that Kanao has warmed up a bit to this game– represented by an acknowledgement of it and giving out the OK for it to be streamed, discussed and such– because there is true value in this game, to the point where I don’t want to make any sweeping conclusion about what is presented here. This game, these ideas, they all breathe. The last piece of imagery we left with is a return to the womb– because within, one gestates, lives, and breathes, still– still human, still alive in its ugliness, but not having to engage with the natural order of violence that permeates the human race outside of those walls. When there is nothing left, there is silence, a silence that is so very empty. Serenity.